‘Never turn down an offer’ – but what if there is no room on the table?

To accept, or not too accept? That is the question.

As humans, ‘time’ is one of our most valuable commodities. But as academics and researchers, it is also one of the variables that is often very hard to come by. We regularly encounter propositions of extra work that, while offering potentially fruitful personal or career developments, come at the sacrifice of time and energy and can become incredibly damaging both physically and mentally. In this article, Dr. Liam Hobbins talks about the strategy he learnt and now uses to help ‘weigh-up’ whether an opportunity is right for him or not. Read on to find out more.

‘If somebody offers you an amazing opportunity but you are not sure you can do it, say yes – then learn how to do it later!’

Does this sound familiar to you? You may have heard this infamous quote by Richard Branson, known as the founder and ‘Dr. Yes’ at Virgin Group. These words are applicable across industries, from the business sector all the way through to higher education and academia. How often have you found yourself being offered an exciting opportunity that, while it will stretch you physically and mentally, may provide a unique opportunity that is impossible to say no to? A unique opportunity that may, in the long-term, facilitate further development in your research and career trajectory. Just the thought of turning down an offer may fill you with early-onset regret, negligence, a sense of laziness and a feeling that others may be gaining an advantage by accepting such offers. These feelings, and the reason for them, will vary from one person to another. For example, one may feel they cannot turn down an opportunity through;

· Fear of missing out,

· Guilt of letting down a colleague,

· Anxiety that you won’t be asked again if you say no to begin with,

· Misbelief that you need to take every opportunity to succeed in academia.

For such a wide-spread issue within our industry, it is somewhat of a grey area; often not discussed, yet widely judged.

“Most of the time, these offers come from persons further along their career path, further along the academic trajectory or higher up within the industry... [which] makes the offer even more tantalising, potentially glamorous, but even harder to turn down. ”

When it comes to offers, I am referring to things such as lecturing (if this is not a mandatory responsibility in your contract), guest presenting (not as educational as lecturing, rather informative) peer-reviewing manuscripts, laboratory testing, study participation and so on. The list is endless, and the offers received are likely dependent on the stage of your career and situations you put/find yourself in. Most of the time, these offers come from persons further along their career path, further along the academic trajectory or higher up within the industry hierarchy, including your supervisor(s), researchers within your department, or senior collaborators. This often makes the offer even more tantalising, potentially glamorous, but even harder to turn down.

Irrespective of the context, there is one recurring factor: all of these will require some volume of effort, energy and time from yourself.

Some individuals may feel that all of the aforementioned offers are just as important as each other, and in fact should be accepted when received. However, given the vast demands and pressures on academics, it can become almost too easy to spread yourself too thin. Taking on opportunities that are perhaps not worthwhile could negatively impact your current workload, and decrease your productivity and efficiency relating to tasks you have already been assigned. Specifically, it may take away time and energy you planned on spending in the lab or writing your thesis or manuscripts. It is plausible to suggest therefore, that such a problem is a key factor in exacerbating any issues with ones mental health, which, in itself, is a conundrum that is becoming an increasingly big issue within its own right (Seaborne, 2020; Woolston, 2020). Taking this a step further, then, it could be argued that there are often too many offers that one cannot decline, and the influx of subsequent roles/tasks can ironically lead to declines in one’s progress and development.

“...such a problem is a key factor in exacerbating any issues with ones mental health, which, in itself, is a conundrum that is becoming an increasingly big issue within its own right...”

Does this story sound familiar? Does it resonate?

If so, why not leave a comment at the bottom of this article, or contact us directly here. If you are interested in writing an article, just drop us a message!

For context, I would like to share two example offers I received during my PhD; one I accepted and one I declined.

Beginning with the latter, my PhD was industry funded. Part of my contract was to be present and work at the centre of my industry partner one day per week during my contract. My roles and responsibilities here are not so important, but on occasions, there were times when I was offered an additional day of work. I usually said yes, but unfortunately, and as much as it pained me, I did decline a few offers of ‘extra work’. Not only did I consider my colleagues great friends, I also enjoyed my role at the centre very much, so it was hard to decline. I didn’t want my industry partner to think I did not want to work, and I didn’t want them to think they could not ask me again in the future. It made me feel as though I was being lazy, whereas realistically, I was just being honest. Deep down, I knew that on some of these occasions, I really had to work on my PhD, and fortunately, the industry partner completely understood the situation, so my decision did not impact our ongoing relationship.

One offer I received and accepted was the opportunity to peer-review a manuscript submitted to a journal. At the time, I had not done this before; I did not really know the process, and in all honesty, I was not sure what I would get out of doing so. Fortunately, the offer came from my PhD supervisor, who kindly took the time to explain and demonstrate the process. For PhD students and early career researchers/postdocs, peer-reviewing for journals is an extremely rewarding experience, however, it does require some effort to be involved. As the manuscript I was invited to peer-review was within my ‘expertise’ and my supervisor reassured me that this will be a good thing to do, I took it on. I probably spent too much time peer-reviewing this manuscript, but as a first attempt, I was not to know, like many others, what it really takes. I ended up peer-reviewing several manuscripts for various journals during my PhD, and I can honestly say that accepting these offers (…I did reject some) was very rewarding for my development as a researcher.

The offers we are exposed to are countless. While some offers are incredibly enriching, fulfilling and sometimes highly prosperous, our ability to perform all of them is limited. As academics/researchers, ‘time’ is one of our most valuable resources but is the one resource that is often so hard to come by. Damaging effects both mentally and physically (e.g., burnout, chronic fatigue, depression) are all to easily related to the sheer workload we become accustomed to.

So, what if you could actually reply ‘sorry, but no, I won’t be able to do this’ when you think you should not or cannot?

It is most likely a trait of mine, but I always heavily weighed up the pros and cons of an offer before accepting or declining during my PhD and continue to do so on a daily basis one year on working in the publishing industry. During this year or so ‘after’ academia, I have reflected more than I have ever imagined. Could I have done this or that differently, which I am sure every doctorate contemplates after their PhD. However, a large proportion of my reflection has surrounded the decisions I made in response to offers, and how they have, or could have, helped me get to where I am now. The purpose of this article is to highlight a) why and how I weighed up offers of amazing opportunities and b), how and why you could incorporate the strategy.

Now, one may be reading this and thinking, ‘so what?’. After many years of reflection and development, I have tried to optimise a strategy to be used when deciding on offers of amazing opportunity come up.

The Strategy.

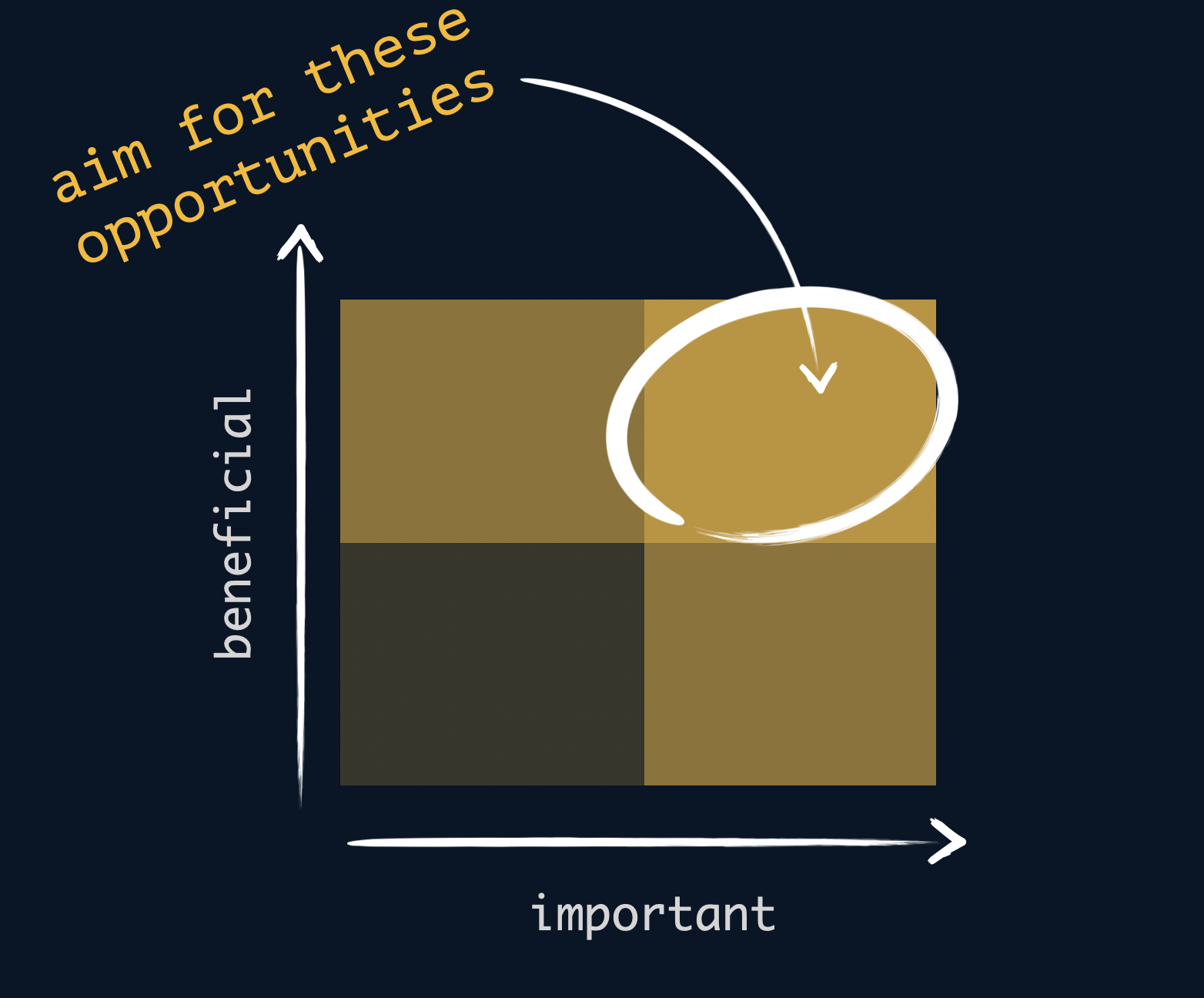

An adaptation of Eisenhower’s ‘urgent - important’ principle

You receive a decision, how do you decide if, right now, this is for you to accept? Let’s imagine there are two strands to this strategy, the first being ‘when will you be rewarded?’. The scale for answers to this question range from: never, today, tomorrow, next week, next month, next year, in 5 years’ time and so on. Take a step back. The second strand asks, ‘what is the type of the reward for saying yes?’. Possible answers here include, but are not limited to, no reward, potential time savings, monetary reward, personal development and so on. It is important to understand that where the offer falls on each strand is relative to you, even if the offer is the same as what someone else has received. Once you have decided where the offer falls on both sets of strands, do you believe, amongst all of your current tasks, that right now, you should accept or decline the offer? Incorporate both strands equally, realising that ‘no’ is an option here. For ease, you can employ a scale on both strands (e.g. 0 to 10 as highlighted below). Simply multiple the numbers generated on each strand to identify the total value of the opportunity you are given. The strategy section is very much akin to Eisenhower’s famous ‘urgent – important’ paradigm used by many when assessing the activities for which their attention should be focused on. It’s a similar sort of principle.

Is it for you?

You may have already heard of this strategy, or may even be incorporating it currently/previously, but it can be applied to any offer. It could help to really identify that, should a reward be realised, when this may be of greatest benefit to you. Likewise, if you feel you cannot accept an offer, this strategy may reaffirm this, highlighting that the reward is too far away or not up to the standard you wished.

Why it worked for me.

Overall, this strategy has substantially helped me understand why declining offers can actually be advantageous in industries where it is perceived as a negatively. Furthermore, it has helped me realise that even when I thought a reward had already been received, a secondary reward was further down the line. Here I am referring to the manuscript I peer-reviewed, which happened to be from the journal of my first and current employer post-PhD. Some would argue this is fate but having this opportunity to participate and understand the system which I now use as a member of the Editorial Office no doubt played to my strengths during the interview and subsequent onboarding process. Initially, I took on the peer-review assignment to develop further as a researcher and gain an understanding of the publishing world, but I got much more out of it. So bear in mind that how you envisage a reward being received and the extent of said reward, may also differ to what and how you are rewarded.

Disclaimer.

To conclude, I would be in denial to say that I do not hold any regrets, and I was and am not always correct with decisions made. This article is also not an attempt to convince you to accept or decline certain offers, nor damage the quote from one of the richest and powerful men on earth, just contemplate deeply before you decide. Importantly, the decision strategy will vary between how you interpret it and the next person.

Written by: Dr. Liam Hobbins (@LiamHobbins)

Edited by: Robert Seaborne

Interested in writing a piece? Just drop us a message. We are happy to discuss any ideas or articles however complete or ‘rough and ready’. Our articles come in all formats (anonymous or not), on a range of subjects, aimed at undergrad through to professors and across disciplines, industries and careers.