Handling Your Shortcomings: process more than product

We are always in the pursuit of trying to answer the currently unanswered. You face the inability to resolve these answers for long periods of time. You find yourself identifying flaws in your own intellect, finding errors in theories, all the while constantly attempting to fill massive gaps in your knowledge. The recurring encounter with such moments of insecurity, doubt and inadequacy are psychologically damaging leading to feelings of imposter syndrome, damaging your confidence and restricting your desire to explore your research further. Read how Robert encountered this during his PhD/postdoc and what helped him to control this scenario.

As a fresh-faced PhD student, I was nervously enthusiastic about diving into the world of molecular physiology, to try and uncover the currently unknown and produce some exciting research. The idea of discovering some new information about the way our human bodies worked (even if only a very small or abstracted finding) was what excited me about going into my PhD and undertaking a long period of directed research. I perhaps naively built up a falsified vision of identifying such a fascinating finding on a regular (or semi-regular) occurrence and utilised this idea performance guided philosophy as a source of motivation for my work. Conversely, what I hadn’t anticipated and what I was ill-equipped to handle were the many (many) encounters I had with my intellectual flaws, my lack of basic or fundamental knowledge in a given subject or the (many) gaps in my academic capability, and the damage this had on my mental health, mindset and psychological landscape.

I would be sat in departmental or laboratory meetings listening to other researchers presenting data for studies and experiments they had been conducting. It would all be built on the basis of fundamental physiology (before progressing into more complex science), with assumptions made based on this very fundamental knowledge. Within these meetings there were some researchers with more experience, or some further along their career path and others who had just started. They would all hold interesting debates with one another based on the foundation of shared knowledge they had of this subject. Asking pertinent questions to one-another, drawing up interesting theories and surmised potential hypotheses. The issue was, that I didn’t know any of this fundamental knowledge and these topics, conversations and debates became a cause for concern, feelings of nervousness and worry.

“what I hadn’t anticipated and what I was ill-equipped to handle were the many (many) encounters I had with my intellectual flaws, my lack of basic or fundamental knowledge in a given subject or the (many) gaps in my academic capability, and the damage this had on my mental health, mindset and psychological landscape”

There would be times in the lab where I would be trying to dissolve and dilute powdered chemicals into a specific concentration solution. I would sit there for hours trying to work out what to do and how to do it. Other PhD students, post docs, master students and even undergraduates would come into the lab, perform the same task without any apparent issues and leave with me still struggling. How was I a PhD student, and yet couldn’t perform basic laboratory tasks?

Even when reading articles in my own field of study, I would come up against ideas, theories, and scientific knowledge that I had absolutely no idea about, nor much of a clue as to what was being discussed. This was supposed to be ‘my field’ of research, and yet, I didn’t know anything about it.

Does this story sound familiar? Does it resonate?

If so, why not leave a comment at the bottom of this article, or contact us directly here. If you are interested in writing an article, just drop us a message!

The psychological effect these encounters had, may have only been relatively minor when taken on an individual basis. You make allowances for the fact that you don’t know something in a specific field, or you aren’t very good at reconstituting chemicals for example. But as these events start to accumulate, the frequency for which you experience them increases. What began as ‘one off’ exceptions were now becoming daily occurrences and the psychological impact of this was intensifying and accumulating further.

As my PhD progressed, I encountered such events on a more frequent basis, becoming more aware of when they were occurring and more aware of the effect of them. Initially, I would become embarrassed by these moments. When faced with a stark misunderstanding or gap in my basic knowledge of my subject. For example, I would inwardly become self-conscious, almost ashamed and guilty of this fact. Over-time, this then led to a more concerning thought as to whether I was actually skilled enough to undertake a PhD. As these encounters accumulated, I began to question whether I am ‘talented’ (more on this in a separate article), knowledgeable or philosophical enough to pursue this course of work. This became massively damaging to my self-confidence, which in turn affected my confidence in my ability to perform my work. I began to second guess everything I did. I sought to take the ‘easier’ route around work, or tasks I needed to undertake to avoid these difficult situations arising again. And very quickly got lost in this fog of self-deprivation, where I was almost pre-empting the next time, I would encounter such a failing in intellect or research/academic ability.

As these psychological issues unravelled, I become more obsessed with the PhD itself. My philosophy to life, and to my PhD at the time, is ‘when the going gets tough, the tough get going’. So, what proceeded, was for me to spend longer and longer in the lab and more and more time spent reading. Counterproductively however, this only exacerbated the issue. As my brain, starved of sleep, rest and recovery, began to become lethargic, slow and unproductive, the issues augmented. A cycle of negativity. Somehow, whether it be due to exhaustion, fatigue or through some other means, this spiral of negativity soon began to ease up. And through no means of my own, these issues became a lot more manageable. On the periphery, I believed I had overcome these issues of self-doubt, imposter syndrome and anxiety for good. And that I had had my fair share of experience with these psychologically damaging factors. I was mistaken.

I took the challenging decision to change fields for my postdoc, moving from a largely physiological PhD, and department, to one steeped in molecular and functional genomics. This was a conscious choice, one that I had taken as I knew I wanted to learn more about functional genomics and gain a greater appreciation and skill set for this field of work. Ultimately, I had pushed myself further out of my comfort zone (career-wise) then I had ever done before. I was now coming up against an entire field of work, fundamental information, basic science, new methodologies and advanced research that I had never encountered before, and it didn’t take long before my insecurities, feelings of imposter syndrome, lack of confidence and fear surfaced again. Although this time it was more intense, as now I was a postdoc. I was considered more experienced. I was supposed to be more skilful. More intelligent. The cycle of negativity, that I thought had been buried for good, was back.

It was at this point I picked up and read a series of eye-opening books (see below for details), and the penny dropped for me. Fundamentally, I realised that the overall performance outcome (research paper for example), isn’t necessarily the main provocative for undertaking a PhD, a postdoc, or any other form of constructive, intense training. It’s the process that is the most important factor. The pathway that leads to the performance outcome, is a process of failing, learning, adapting and developing. And it is precisely this pathway of development that is the best and most constructive part of what we do. We undertake a PhD, or a postdoc or a career in research to continually try and answer the unanswered. But in order to do this, we must continually develop the stuff that we don’t currently know ourselves. We therefore undertake a career in self-development. It is therefore not about the end product, but how much we are willing, able and courageous enough to continually learn.

This therefore, is the main crux of it. Learning, and having the courage to continue to learn in the face of setbacks, failures and flaws, is crucial. The process of learning is far mor important, far more constructive, than the end performance variable.

Put in a different context, this idea relates entirely to that of the fixed vs growth mindset, detailed brilliantly by Carol Dweck in her book ‘Mindset’. Carol describes how a growth mindset is a necessity for building success. When faced with the realisation of failure, lack of knowledge or inability to a given task, a person with a growth mindset is able to navigate this scenario and use it as a positive to spur them on. A growth mindset is able to accept that they may not currently know something but that, given time, patience and practise, they will develop the ability, skill or intelligence to learn it. This growth mindset will then continually recycle this process of development, to continually progress through to success.

I wasn’t born knowing how to dissolve chemicals to create a specific concentrate solution. Nor was I able to remember every reaction, substrate utilised, rate limiting factor and by-product created of the Krebs cycle. But what I didn’t realise during my PhD and early period of my postdoc, was that this is not a negative. This isn’t a slur on my ability, nor a smear against my academic potential. This is simple an opportunity to learn, adapt and develop. When thought of in this context, these events or opportunities to develop, serve as a reminder that we are in fact on the correct path to success. As J. K. Rowling once applicably said:

“Some failure in life is inevitable. It is impossible to live without failing at something, unless you live so cautiously that you might as well not have lived at all—in which case, you fail by default.”

The idea that we need to know everything is tricky. It is subconsciously built into the culture of academia and is present in the wider spectrum of life. Its false. Nobody knows everything. There are many out there who present like they do. They project a facade of innate knowledge, talent and expertise for everything. This again, is false. Nobody is able to know everything, about everything.

“The ability to learn, and continue to learn in the face of failings, flaws and setbacks, is more important, more productive and more gratifying, than the product for which you originally strive. ”

Mindset by Carol Dweck

Professor Dweck is a psychologist from Stanford who has spent decades researching the ideology of fixed vs growth mindsets, and the relation these have on performance, in any context of life (sport, arts, academia etc.). The most applicable part of her book in the context of this article, is the idea that upon encountering a failure or setback in knowledge, those with a fixed mindset usually give up. They believe that they simply do not have and are not able to develop the skills or knowledge required to overcome the obstacle. Those with a growth mindset, however, see this obstacle as a challenge and one that with careful and directed practise, patience and a bit of desire, they can learn the necessary knowledge and or skills to navigate passed.

Bounce by Matthew Syed

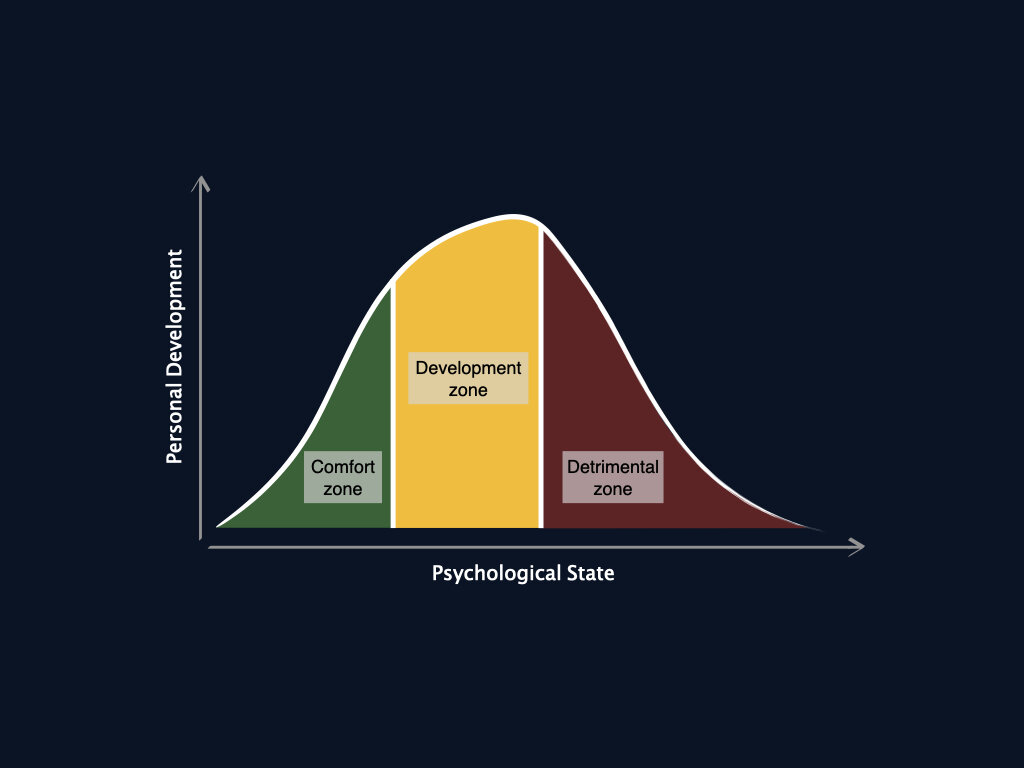

This brilliantly written book revolves around the idea of talent, and the misnomer that talent is the root cause of all success. He talks about his experiences in a sport (table tennis) at a young age, and how many factors came together to provide him with the ideal setup to be a world-class table tennis player. His book challenges the idea that talent is an innate capability, suggesting that, in fact, deliberate practise and pushing yourself out of your comfort zone to encounter periods of development are key to success. If this book interests you, also read ‘The Art of Learning’ by Josh Waitzkin.

The Score Takes Care of Itself by Bill Walsh

This is a classic book when talking about process over performance product. Bill Walsh, considered to be one of the most influential and successful American football coaches of all time, was head coach of the San Fran 49ers during a period in which they won 3 Super Bowls. His book is a meticulous account of how he created a successful organisation by installing a philosophy of process over outcome into the setup. How taking care of every little process to do with the club, will all accumulate together to create a successful outcome. He stresses the importance of the process, for it is here that development, adaptation and installation of correct habits takes place. When all of these processes are correct, Bill suggests that the performance outcome takes care of itself.

Written by Robert Seaborne

Twitter: @RobbySeaborne

Edited by Laura Davorn